The writer’s name is withheld by request.

No puedo (I can’t), my parents would say anytime I wanted to go somewhere far from home. I was seven when I first realized my life wasn’t the same as the other kids my age. I asked my parents for a trip to the zoo. No puedemos, my parents told me. Not because they didn’t have the money, not because they didn’t have transportation, but because they were scared of our family getting broken up.

Since the beginning of my life, my older sister has always cared for me, looking over me while my parents worked from dawn to the dead of night. Working to provide for me and my sisters. My parents came to this country when they were only kids. My dad, at the age of 17, decided he needed a change to have a better life later on and brought my mother with him. A better life, my parents thought, but they would later realize that coming to America wasn’t selfless but a decision that came with consequences.

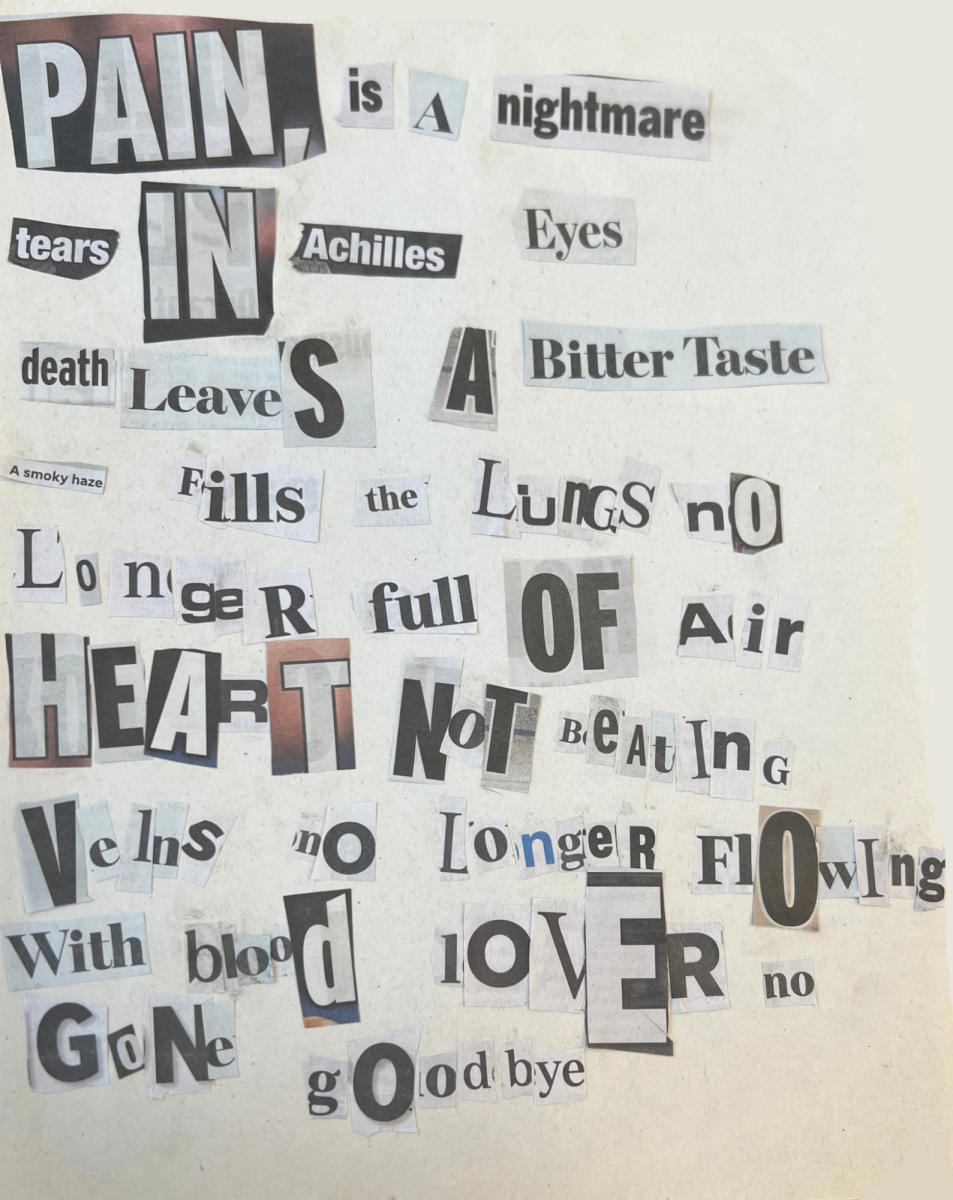

My parents are two of many immigrants who came to America to have a better life. Leaving behind family, friends, and everything they have ever known for a place that would make them feel alone and different. They sought a better life in hopes that my sisters and I wouldn’t have the problems they had growing up. Both my parents came from poverty and struggled even to have food on the table. Their decision came from the way of living in Mexico. I was ten when my mother decided she needed to register to become a resident after 16 years of living in the U.S. She decided she needed this. My father disagreed because he was scared of the risk of getting sent back—the fear of not seeing his children anymore. Months later my mother got Residency while my father was denied. We received the news on his birthday that he would have to leave the country. I could feel my heart swell and race, not remembering how to breathe at that moment. Despite my mother feeling joy about finally being able to see her family after 16 years, she felt sad for my father, who would now have to live in fear. The same fear he first had when going through this process of citizenship.

It has been 31 years since my father has seen his family while living in America. His father, my grandpa, died a while after he came to America. I remember seeing my father have to grieve when I was only eight years old. Knowing we wouldn’t be able to go to his father’s funeral, knowing his mother would be alone. No puedo, my father told me when I asked him why we couldn’t go to see his father. No puedo, my father told me when I was eleven years old when I asked him to go on a trip with me. No puedo is the only answer I got when it came to traveling or anything that would risk him being taken away from us.

I am now 16 years old, and immigration isn’t a small problem. At the beginning of this year, with our new president, immigration was on my mind. Despite being “safe” from it for 31 years, this year feels different. Beginning in January, border control started taking immigrants, breaking up families from Bakersfield, and spreading it around California. While I can understand the need to get rid of the people making this country dangerous, I can also understand the need to protect field workers, people who work in packing houses and do the jobs most people won’t. Why can’t people can see that immigrants aren’t “dangerous aliens” but hard workers? No puedo, my father tells me every time there’s a need to leave the house. No puedo, my father tells me when I tell him going to work isn’t worth risking our family getting torn apart. My family, especially my father, now lives in constant fear of one day getting a call that my father was taken by immigration. He won’t leave the house unless it comes to work. Despite being scared, he says he needs to provide for his family. No puedo my father says – a consent reminder that we have to live in fear.